Why Intelligence Still Deserves Discussion

In my previous post for the Insights blog, I wrote about the importance of talking about intelligence. Among the reasons I discussed was the finding that IQ is correlated with many biological, sociological, health, economic, and personal outcomes.

The Expected Correlations

Some of these correlations are expected. For example, the original intelligence tests were designed to predict success in school, and so their creators purposely chose tasks and questions that successful students performed well on. This makes the correlation between IQ and educational outcomes unsurprising—even today with tests that are very different from the first intelligence tests.

The Surprising Correlations

But there are some correlations that are surprising. People with higher IQs are less likely to die in a car accident, have better marksmanship with firearms, and receive fewer mental health diagnoses. Unlike educational outcomes, intelligence tests were not designed to predict these things—and yet they do anyway. This fact can make it very tempting to portray intelligence as being the variable that can explain everything.

The Limits of IQ

Just as ignoring intelligence would be a mistake, putting too much emphasis on intelligence causes problems, too. Yes, IQ predicts many life outcomes, but always imperfectly. In all three surprising examples here, the correlation between intelligence and the outcome is less than .20. If the relationship were perfect, then the correlation would be 1.0. There large gap between the observed correlation and a perfect correlation shows how much room there is for other variables to exert an influence on life outcomes.

Beyond Either/Or Thinking

This means that intelligence is not everything. To have a full understanding of people, it is valuable to gather other information. But this is not an either/or choice to make. Rather, it is a decision to value intelligence and other characteristics.

The Value of Incremental Validity

The best traits to focus on will be those that provide information that IQ and cognitive variables do not. Psychologists call this “incremental validity,” and it means that adding the new variables will improve our understanding and our predictions. The variables with the most incremental validity will be non-cognitive (because IQ already covers that) and important in daily life.

Personality Traits Add Predictive Power

Personality is a strong candidate. By definition, personality is not cognitive, and so its correlations with IQ tend to be weak. Personality variables, especially conscientiousness and openness to experience, have shown some ability to predict life outcomes. These findings make intuitive sense. People who are high in conscientiousness tend to follow social norms, have high impulse control, and practice delayed gratification. Openness to experience makes someone willing to try new ideas and experiences, which may make them try different ideas to solve problems. These traits are useful for someone trying to build a successful career or a strong marriage.

Personality + Intelligence: A Stronger Picture

Both personality and intelligence predict life outcomes. In one major synthesis of previous studies, the correlation between IQ and academic achievement was .42, and the correlation between personality variables and academic achievement ranged from .13 to -.02. But combining the personality variables and intelligence raised the overall relationship to .53. This study is typical in its findings: personality has incremental validity over intelligence alone, but intelligence usually is the work horse that has the strongest relationship with life outcomes.

What IQ Tests Leave Out

The content of intelligence tests provides another strategy for identifying traits that are important to consider. No test can measure everything important, and for over 100 years, intelligence test creators have stated that there are important psychological characteristics that their tests do not measure.

Creativity as a Complement

One common example is creativity. People with high creativity can generate many novel, useful ideas. This is why creativity tests often ask examinees to provide many answers to the same question. For example, on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking, examinees are asked to think of different uses for a common household object, or many different consequences of an event. Examinees receive higher points for generating a large number of relevant answers that are unusual and/or detailed.

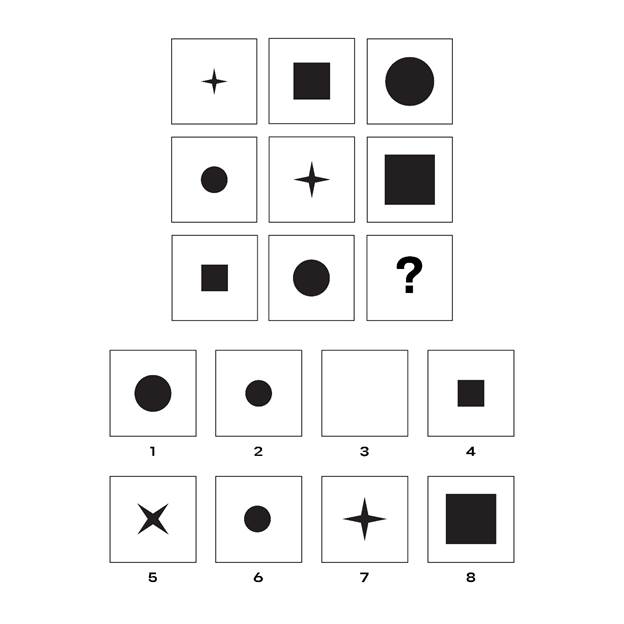

On the other hand, this sort of strategy would be detrimental to performance on an intelligence test. That is because questions and tasks on intelligence tests are designed to have one answer. This can be seen in the image below, which is an example item from the Reasoning and Intelligence Online Test (RIOT). For this question, the examinee must study the 3 x 3 grid of squares at the top and then identify which of the 8 choices at the bottom would complete the pattern in the grid. There is only one correct answer (option 7), and there are no benefits from dwelling on this question and elaborating on the response.

Clearly intelligence and creativity tests measure two separate thought processes. Both provide important insights into a person’s thinking. And if society wants the best problem solvers, it should cultivate both intelligence and creativity.

Emotional Competence: Another Piece

Another behavior that is not measured on intelligence tests is what is popularly called “emotional intelligence.” This is the ability to be aware of one’s own and others’ emotions, manage those emotions, and use the information they provide to make decisions. Because many intelligence scholars do not believe that “emotional intelligence” is a cognitive ability the way that traditional intelligence is, I prefer the term “emotional competence.” Regardless of the term, everyone can agree that intelligence tests lack any content designed to measure the tendency to use emotional information to solve problems.

Emotional competence is associated with better academic and job performance, but the association is weak—usually with correlations in the low .20s. Moreover, emotional competence/intelligence seems to be another way of measuring personality traits, especially conscientiousness. Emotional competence seems to provide little incremental validity beyond the information that personality provides. While “emotional intelligence” may just be a repackaging of important personality traits, this does not negate the fact that there is value in understanding people’s emotionality and that this understanding will not come from an IQ test.

Cultural Traits Worth Considering

So far, I have only discussed traits and abilities that come from the scientific literature. But there is no reason why we need to limit ourselves to that. There are many human characteristics that originate in the wider culture that are useful supplements to intelligence.

Wisdom as Direction

I believe that wisdom is a valuable concept to consider. Humans can do amazing things with their intelligence. But if intelligence is channeled into pointless or foolish endeavors, then the benefits are trivial. Video game performance and IQ are positively correlated, but I do not think it is beneficial for society to encourage its geniuses to become video game champions. Coupling intelligence with wise decisions and actions can greatly improve how intelligence is used.

Ethics as a Guardrail

Likewise, ethics is a hugely important consideration for determining how people should use their intelligence. History provides a stark example of the disastrous consequences of high intelligence without ethics. In 1945, psychologist Gustave Gilbert administered a German translation of the Wechsler-Bellevue intelligence test to 21 captured Nazi leaders who were defendants at the Nuremberg trials. Their IQs ranged from 106 to 143, with a mean of 127.6—far above the population mean of 100. These intelligent men ran one of the most horrific regimes ever to take power and were responsible for the deadliest war in human history, which included the systematic murder of 6 million Jews in the Holocaust. The Nuremberg defendants showed that intelligence can be used for evil purposes; strong ethics guiding individuals towards prosocial behavior is vital.

Conclusion: A Fuller View of the Person

is a beginning—not the end—of understanding a person. Personality, creativity, emotional competence, and other traits matter in addition to IQ. An influence from wisdom and ethics can help a person steer their intelligence into beneficial endeavors. In addition to providing a more complete picture of a person, this multidimensional view of people is also far more interesting and informative than focusing on just one trait or behavior. In the next post in the series, I will discuss what the assessment process should look like to produce this multidimensional understanding of a person and how new technology can lead the way.

Comments (0)