Moby-Dick by Herman Melville: “We get it; the whale is white.” J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye: “What a brat!” The Jungle by Upton Sinclair: “Never eating sausage again.”

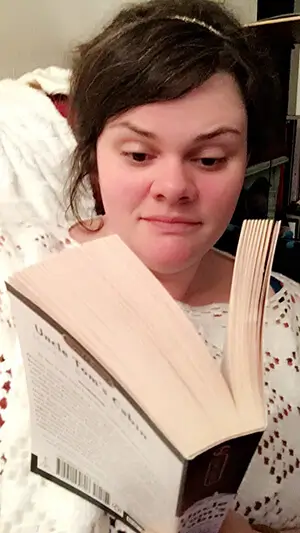

You’ll forgive English teacher Laura Buller for her terse, albeit on-the-nose, comments about iconic works of literature. She was busy reading the next great tome. Buller, who instructs high schoolers in Conroe, Texas, recently became just the sixth person to document and complete the Mensa for Kids’ Excellence in Reading high-schoolers list.

The catalogue of classics is part of a program sponsored by the Mensa Education & Research Foundation to encourage reading. Drawing from National Endowment for the Humanities recommendations, the Excellence in Reading program boasts lists for four different age groups — kindergarten to third grade, fourth through sixth grade, seventh and eighth grade, and ninth through 12 grade.

Her pupils in mind, Buller choose the high-schoolers list. Thumbing through it was no small feat. With some 120 titles, any reader is going to find some works they would not consider page-turners. Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe: “Only one main character — unrelatable.” Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales: “Very slow.” Tell that to the pilgrims!

Buller’s remarks were jotted on her application for completing the program, which nets finishers a commemorative certificate and T-shirt. For months Buller plowed through the titles, noting on her application when she completed a book, rating each on a five-star scale, and, occasionally, providing a comment or two. The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane, four stars: “Nature doesn’t care about you.” The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde, two stars: “So boring, oozing with figurative language.” Save that one, teacher, for the lesson on irony!

Buller found out about the Excellence in Reading Program through a gifted and talented workshop at her school and challenged herself to complete the list in under two years, which she did. Some of the books were familiar; she’s taught Beowulf and Hamlet, for example. Others proved to be pleasant surprises, like The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. As a whole, she especially valued the potential for young readers to be exposed to the greats.

“I think reading is absolutely necessary for our imaginations to grow,” Buller said. “And I think young people don’t read enough already. They need to be able to create a world through a book instead of being shown what someone else wants them to see through film.”

Not that there’s anything wrong with film. The silver screen version of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible was a strong adaptation, Buller’s application notes read.

And what impressions did an English teacher have on the composition of the Excellence in Reading program’s compilation? She was impressed. Pressed for criticism, Buller would have preferred Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis to the list’s The Trial. And one omission she would have included is The Alchemist by Brazilian author Paulo Coelho.

Her favorite from the list? All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Remarque. “When he says, ‘The stars were cold,’ it gave me chills thinking of the horrors of war and how these young men compartmentalized their lives during and after the conflict.”

Her least favorite? That would be the one with a pearly aquatic mammal. “There are three chapters in a row about how and why the whale is white — boring!”

Find out more about the Mensa Foundation-sponsored Excellence in Reading program at MensaforKids.org. The reading lists are long, sure. But it’s certainly an easier chase than Captain Ahab’s.

Comments (0)