The Mensa Foundation Prize is awarded every two years to honor research that changes the way the world understands human intelligence. In 2025, we celebrate Dr. Fredrik Ullén, a scientist and pianist whose life’s work illuminates how practice, persistence, and ability intertwine to shape both the brain and the human story of mastery.

Learn more about past Mensa Foundation Prize Laureates here,

Rethinking Intelligence Through Practice

Ullén’s research helps us see intelligence in a new way. For years, people have debated whether greatness comes from talent or hard work. His work shows us that it is neither one nor the other. Practice matters, but it does not land the same way for everyone. Two people can devote the same hours to mastering a skill, yet their progress unfolds differently. The difference lies in the interplay of ability, motivation, personality, and environment.

This is not the old gift versus grind debate. Ullén’s research points to something far more dynamic. Practice reshapes the brain, reinforcing pathways like backroads turning into highways. Intelligence amplifies practice, and practice expands capacity. It is not either-or. It is a duet.

Why His Work Matters

For educators, parents, and learners, this matters deeply. It challenges the myth that success is only about grinding out 10,000 hours or being born with a rare gift. Instead, it tells us that mastery grows in many ways, shaped by biology and choice, persistence and environment. Excellence does not follow a single script.

Perhaps the greatest gift of Ullén’s work is hope. Hope that effort matters, even if it looks different for each of us. Hope that intelligence is not limited to one definition or confined to one pathway. Hope that the arts and sciences, when seen together, can deepen our understanding of what makes us human.

Living the Research

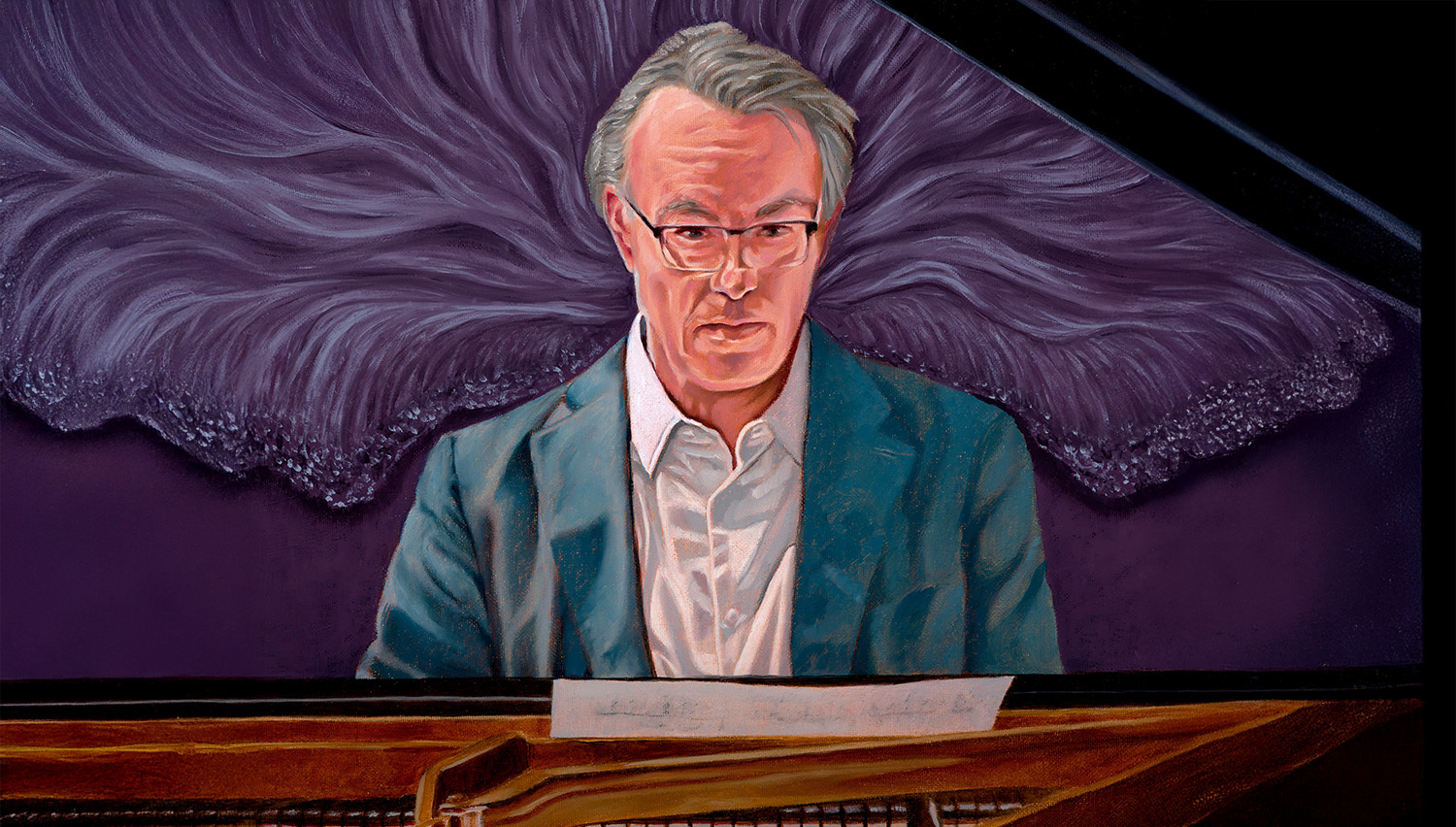

And this is not only theory. Ullén lives what he studies. As the first pianist to record Sorabji’s 100 Transcendental Studies, an eight-hour feat of artistry and endurance, he embodies the same persistence and complexity that defines his research. His dual career is a reminder that intelligence is not confined to a lab or a score. It is something we practice, perform, and refine across the whole of life.

A Prize That Reflects Our Mission

By honoring Dr. Ullén, the Mensa Foundation also affirms our mission: Unleashing Intelligence for the benefit of humanity. His work demonstrates that intelligence is not just a test score or a label. It is something we live into, shape, and expand throughout our lives. It is the meeting point of our biology, our choices, and our environments.

That is why we celebrate Dr. Fredrik Ullén as the recipient of the 2025 Mensa Foundation Prize. His life and work remind us that intelligence is not static. It is a living, evolving force. And when nurtured, it can enrich not only our individual lives but the world we share.

Comments (0)